Introduction

In the early weeks of lockdown, dread moved like fog, slowly, but without escape. The world paused.

I’m not what most people would call “creative.” My mind craves logic, structure, systems. But in that eerie stillness, cut off from routine, noise, and people, I needed somewhere to put that energy. A place to focus, not just pass time. Blender became that place.

It started as a curiosity, a challenge. Then, unexpectedly, a kind of therapy.

I’m a film graduate. I’ve always admired the craft of image-making, particularly cinematography, framing, lighting, blocking. I understood the theory. But I couldn’t draw. I couldn’t paint. I wasn’t a “maker.” Game design fascinated me, but it always felt out of reach, too artistic.

Then came the silence of lockdown. No distractions. No excuses. For the first time, I could learn for the sake of learning, without pressure, without a goal, without an audience.

Blender was a space. To build, to break, to render something and say: I made this.

What follows is a selection from that journey, not a portfolio, not a greatest hits reel, but a kind of visual journal. These renders aren’t perfect. Some are messy. Some are half-finished. But all of them hold something: a mood, a memory, a moment of focus in the fog.

Most are studies in light, space, solitude. Each one taught me something, not just about 3D tools, but about attention, persistence, and the quiet joy of looking closer.

This is what I made, when the world stopped.

Phase 1 - Loops & Movement: Learning by Repetition

There’s something universally compelling about loops: short, seamless animations where cause and effect fold into one another. You don’t need context, plot, or meaning. They’re visual fidgets. Smooth, complete, satisfying. For someone like me, who finds comfort in structure, this felt like the perfect entry point.

No clutter, no theory. Just clean repetition.

So I began here: shapes in motion.

This phase was less about design and more about feel. Learning timing. Rhythm. Weight. Finding where motion starts, where it resolves, and how it all loops back on itself.

Cheese Stack

Messy, basic, but deeply satisfying.

Probably my favourite animated piece I’ve done. It’s incredibly basic, but the motion is smooth and almost hypnotic. The colours contrast well, and it scratches that itch. There are a few issues though, like the lack of a loop. But for one of the earlier pieces, I was pretty happy with it.

Ball Slice

One of the cleanest loops I made in this phase, timing-wise. The motion is slick. There’s a satisfying release in the slice. But this taught me a deeper lesson: motion alone isn’t enough. If your materials feel wrong, your colours feel off, the whole effect breaks. A good animation is invisible when it works and distracting when it doesn’t. This was my first taste of that balance.

Ball SeeSaw

Probably the most viscerally satisfying. The anticipation. The moment the ball hits and tilts the container. This loop taught me about easing, how acceleration and deceleration can give weight to something weightless. It’s not photorealistic. But it moves in a way that feels real (if you ignore the wrong physics).

Abstract Ring

This was a leap. My first real experiment with modifiers, arrays, deformers, procedural motion. The shape spirals endlessly, like it’s pulling space around itself. More importantly, this is where I started thinking about lighting. I played with a rudimentary three-point setup: cool tones on one side, warm on the other, white light as the base. It didn’t “work” exactly, but it gave me a glimpse into how light could shape movement.

Bubble Hoop

This one was about physics, simulating a soft body as the bubble passed through a rigid object. To make the motion clearer, I added small “balla” for visibility, which I now regret; they distract from the softness of the main form. The speed is slightly too fast, and the background colour is overwhelmingly harsh, not the calming, satisfying tone I was aiming for. This was a clear lesson: too much detail kills clarity.

Floating Shapes

The final loop of this phase. Technically sound, but creatively uneven. The vertical float feels lifeless, but I liked the little spiral of new geometry emerging from the ground, it felt like progress, like creation.

Reflection

Looking back, it’s strange that I started with animation. Movement is one of the hardest things to get right, it exposes every weakness. But at the time, I didn’t know that. I just wanted to make something that looped.

There was a comfort in it. A kind of control. The world outside was frozen, uncertain. But here, in my viewport, I could create motion with intent. I could control when things started. When they ended. And how they returned.

Phase 2 – Realism & Object Modelling: Finding Meaning in the Mundane

Making the imaginary feel tangible.

After a week of spinning spheres and bouncing balls, I felt a shift. Animation had taught me how things moved, now I wanted to learn how things existed. How to give weight and stillness to form.

I needed to find out, could I model something that made someone say, “I know what that is”?

That’s when I discovered the infamous Blender Donut Tutorial. It’s a rite of passage for a reason. As much as it’s mocked, it teaches the entire pipeline: modelling, texturing, lighting, rendering, all wrapped in pink frosting. It was the first time I followed a process and ended up with something that looked real.

After that, I became obsessed with the mundane. Not fantasy towers or sci-fi ships, but everyday objects. There was something meditative in them. Something quiet. Chairs. Tables. Wood. Metal. The real world in fragments.

The Donut

My first milestone. My first taste of Blender’s full creative stack.

UV unwrapping, bump mapping, material nodes, it was like unlocking a secret language. The final render looked decent enough, but what really stuck with me was the process: deliberate, layered, and complete.

Yes, following a tutorial step-for-step can feel mechanical. But this one gave me a framework. A path. It gave me permission to make something without needing to reinvent the wheel.

It was the moment I realised: this might actually be possible.

Chair 1

My first attempt without a tutorial. Just reference photos and guesswork.

What I loved about this one wasn’t the model, it was the act of observing. Suddenly, I was looking at furniture differently. Not as décor, but as geometry: edge loops, bolts, symmetry, shadow. I stopped seeing “a chair” and started seeing construction.

There was pride in this one. Not because it looked amazing, it didn’t, but because it felt real.

Chair 2

A refinement of Chair 1. Sharper materials. Smoother topology. Better lighting.

I started playing with metallic shaders, edge bevels, and subtler proportions. It was the first time I looked at a model and thought: this almost looks intentional. Like something I’d see in a product catalogue.

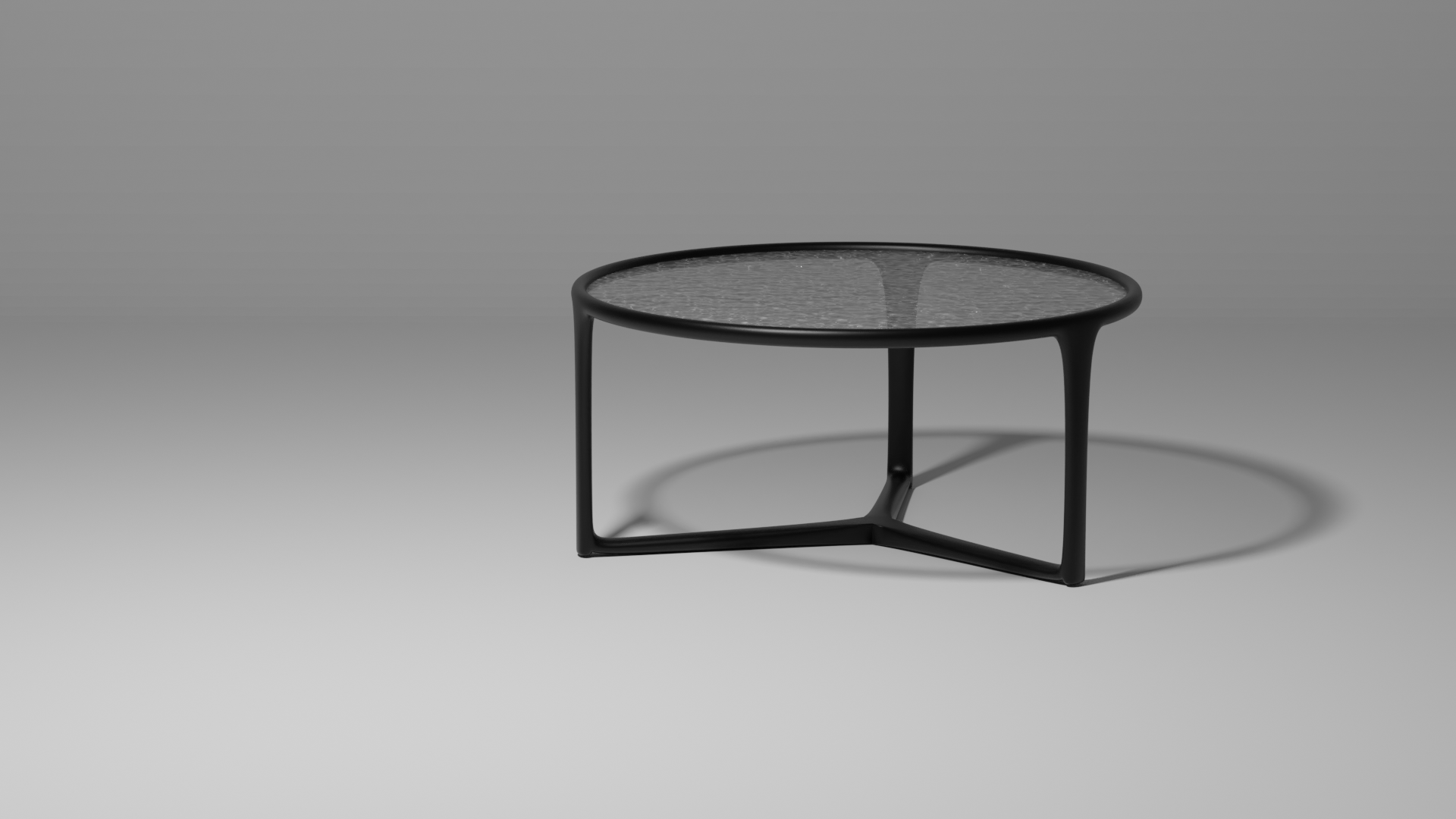

Table

Simple in design. Unremarkable, even. But this one taught me something: Composition is everything.

The model itself was fine, structurally sound. But the materials felt sterile. The glass didn’t catch the light well. The angle was off. It reminded me that modelling is only part of the story. If the camera isn’t right, if the scene doesn’t sell the object, no amount of geometry will save it.

It made me think about films again, how every object on-screen has to feel like it belongs there, in that light, in that moment.

The Well

Another tutorial, this time by Grant Abbitt (Beginner Blender 4.2 Tutorial: Modelling a Low-Poly Well).

Unlike the donut, this one leaned into structure and repetition. Wooden beams. Hexagonal stones. Roof tiles. Every plank a micro-study in placement and balance.

This wasn’t a fantasy asset, it was a lesson in functional assembly. I began to understand how real-world objects are built from layers of constraint. And that, paradoxically, those constraints often make a model feel more believable.

Reflection

This phase wasn’t flashy. There were no glowing loops or bouncy balls. But it taught me to slow down, to look more closely.

In animation, everything is about movement. Here, everything was about presence.

I stopped chasing “cool” and started chasing “convincing.” Modelling became an act of quiet study: noticing how a chair leg curves, how screws anchor into wood, how light bends around metal.

This was where I learned to see not just what things are, but how they’re built and why that matters.

Phase 3 – Light, Space, and Story

Where the world began to feel bigger than my room.

At some point, Blender stopped being something I learned and started becoming somewhere I went.

I wasn’t building objects anymore, I was building places. Scenes. Moods. Not stories in the traditional sense, but something adjacent: a feeling, a fragment, the atmosphere of a moment that might mean something to someone.

This phase marked my first real understanding of cinematography as composition, not just as study. I wasn’t just framing objects; I was framing emotion. And I was doing it through space, light, and absence.

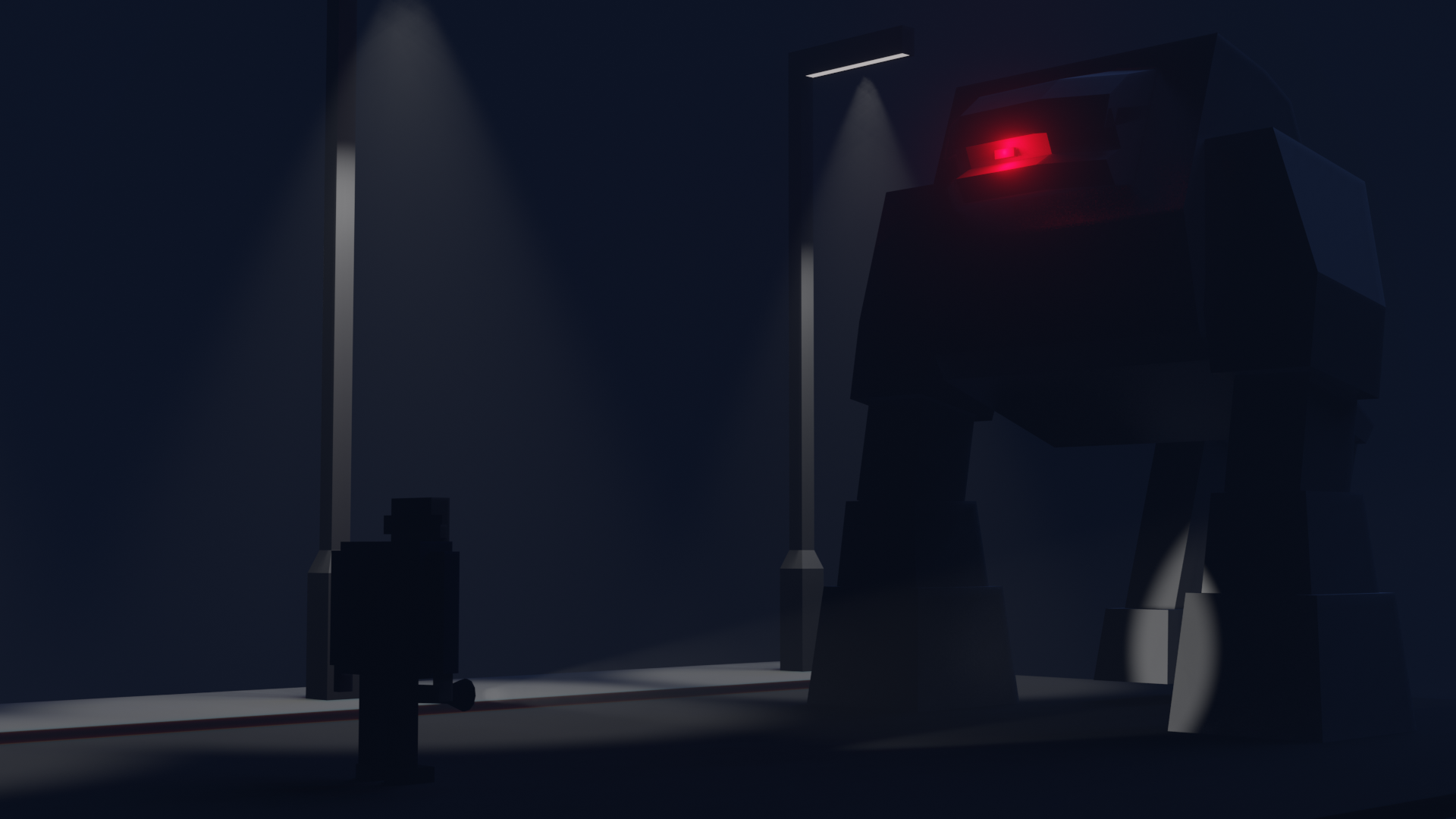

Robot at Night

Tutorial Source: Grant Abbitt – Blender 3 Beginners Guide

This is where everything started to click.

The modelling was simple. The robot, barely detailed. But the lighting, the volumetric fog, the rim light, the cold spotlight cutting through the scene, that’s what made it feel like a moment. The red glow adds menace, but it’s the shadows that carry the weight. I learned that what you don’t show is as important as what you do.

It was the first time I used light not as a technical necessity, but as narrative intent.

Sword in Stone

Tutorial Source: CG Fast Track

This was my first attempt at full-scene blocking. A cave, A relic. Soft fog. I had the ingredients. But something about the scene didn’t land, it felt flat, despite the glow passes and depth of field.

In hindsight, I think I was trying to imitate rather than create. Still, I learned how powerful scale and focal length could be.

Not everything you make will hit. But every piece teaches something.

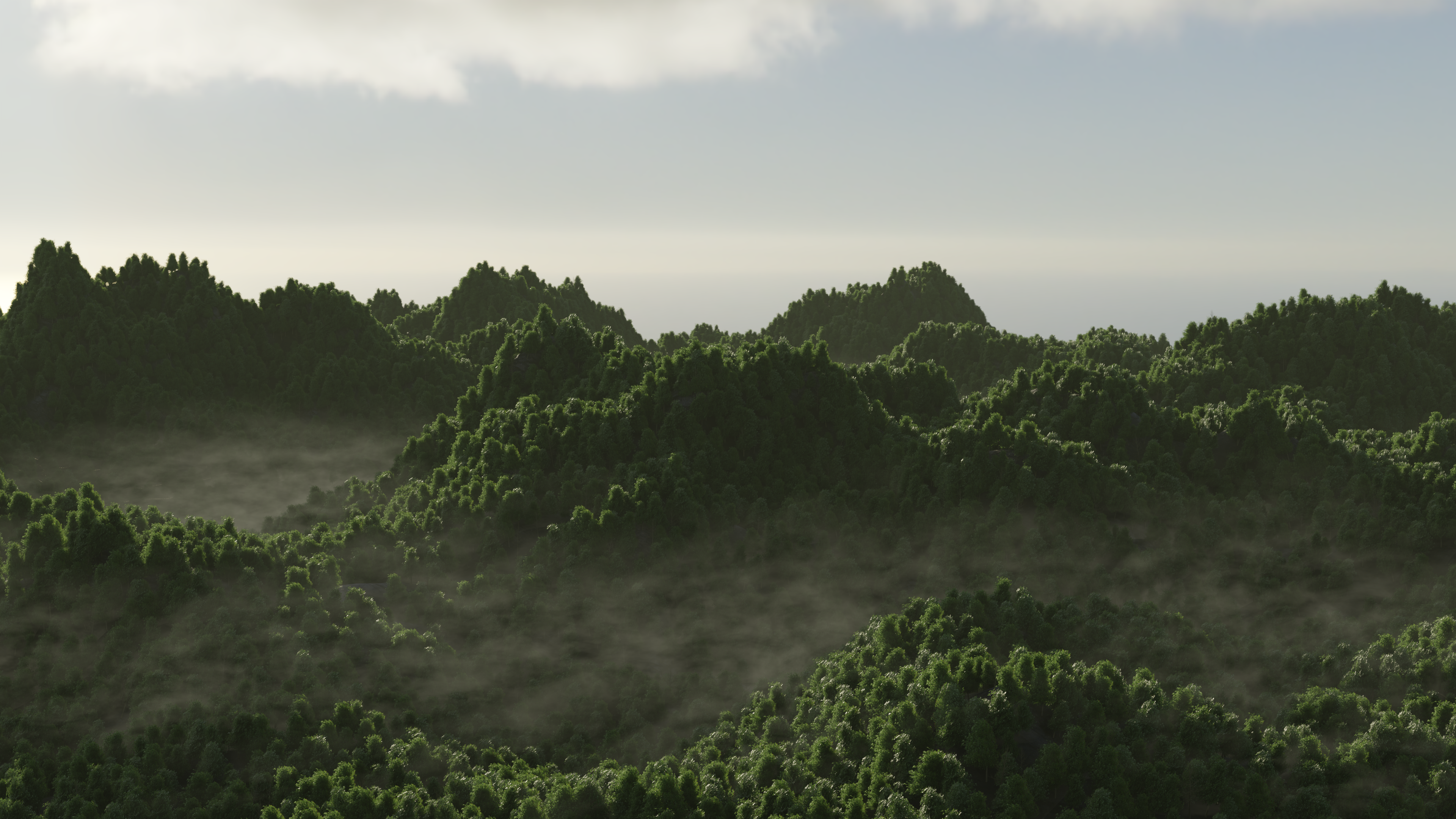

Procedural Forest

This render started as a technical experiment in procedural generation, scattering trees, layering fog, and playing with light. But what emerged was something surprisingly serene.

There was no subject. No center. Just density.

And in that chaos, I had to learn how to guide the eye, how to use light to carve a path through the noise.

It felt like building nature from math. Controlled randomness. It was the first time I created a space I wanted to step into.

Room

This was the first render I’d call a complete scene.

It wasn’t a collection of objects. It was a designed environment, blocked out, textured, and lit with intention. I wanted to create a space that felt cold, barely lived-in, and slightly off.

Reflective tiles. Moving boxes. Modernist stairs that couldn’t quite exist. A low-poly cityscape through the window.

I reused my earlier chair and table models, placing them in a new context. That felt like a subtle creative milestone: reframing old work into new meaning.

It’s quiet. Almost empty. And I like that.

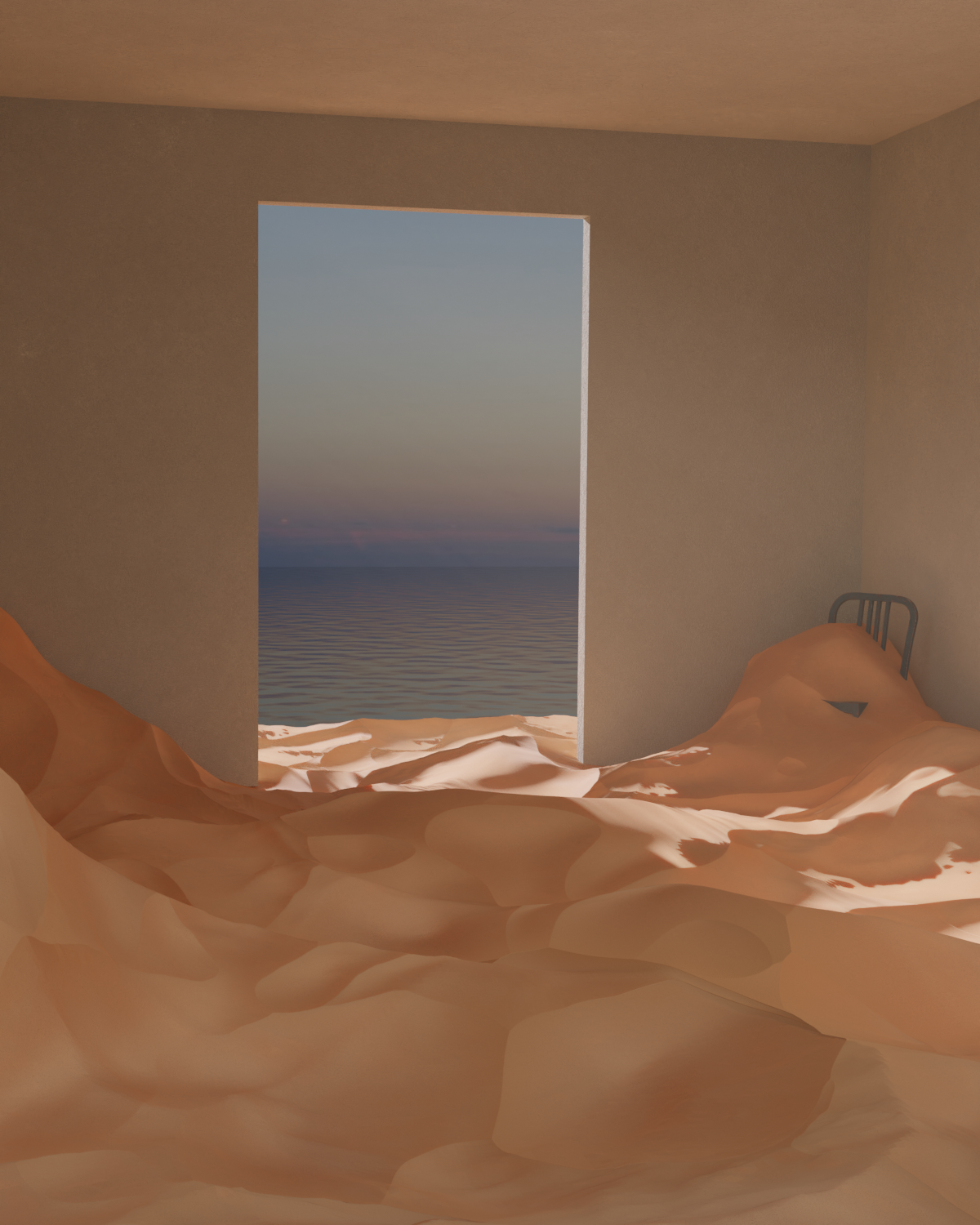

Sand Room

Maybe my favourite piece from this era.

Inspired by a Tame Impala album cover, it blends dream logic with architectural realism: a room half-buried in sand, open to an ocean horizon. It’s abstract, but grounded enough to feel like a memory.

The lighting is soft. The perspective is deliberate.

It taught me that surrealism doesn’t require exaggeration. Sometimes, just putting the wrong things in the right room can create tension.

Reflection

This was the phase that changed my trajectory.

I stopped seeing Blender as a tool and started seeing it as a canvas. A camera. A space to compose with light instead of paint. A place where I could design silence, isolation, and stillness, not because I intended to, but because that’s what I was feeling.

These scenes aren’t complex. But they taught me about tone.

They taught me that a soft edge, a single light source, or a missing detail can speak louder than any texture.

In the repetition of lockdown, these renders became places to go, little cinematic postcards from an interior world.

Phase 4 – The Solitude Series

Loneliness lighting

By now, the Blender tutorials were being less frequented. I wasn’t watching step-by-steps. I wasn’t trying to impress anyone, not even myself.

These renders weren’t just about learning anymore. They were about processing.

About solitude, atmosphere, and building quiet little worlds.

The outside world was starting to stir again, lockdowns lifting, routines returning and I could feel my time with Blender tapering. But before I let it go, I needed to make these.

They’re the most personal.

Gas Station

A single light in the fog. A buried station in a desert no one visits.

This render wasn’t planned. It emerged organically, drawn from techniques I learned while making the Sandroom scene: procedural dunes, atmospheric fog, a solitary spotlight.

It’s sparse. Stark. And I think that’s why it hits.

There’s no story here, but there’s feeling. A last stop before nowhere. A place frozen in time.

This might be the loneliest render I made.

Final Space

A floating Earth. A glowing window. Blackness.

This was the first render where I set out to evoke something beyond the screen, not just a scene, but a perspective. A traveller gazing back at the planet, framed in silence.

I reused an old Earth model and kept the rest intentionally minimal. Just negative space, and soft light gradients.

There’s no detail to get lost in. And that was the point.

This was about absence, the story of what isn’t there.

Snowy Alleyway

Inspired by Liam Wong’s TO:KY:OO, this render is part homage, part imagined photograph. I’ve always loved the tight framing of alleyways, how narrow spaces trap light, isolate movement.

I struggled to replicate the iconic neon glow of Tokyo’s backstreets. Instead, I leaned into cold, snow, fog, steel.

The power lines were a focus: clean and directional. They appear again later.

This scene wasn’t cinematic. It was photographic. A still that felt like a memory I never had.

Hallway

Inspired loosely by Silent Hill and abandoned industrial spaces, this hallway was all about tension through contrast: warm highlights, harsh shadows, decaying surfaces.

Everything here is mine, every bolt, pipe, handle. Even the grime was hand-placed.

It’s a space no one wants to be in and that was the goal. A place that hums low in the back of your mind like a bad memory.

It taught me that dread doesn’t need monsters. Just lighting and intent.

Ruins

This one was chaos by design, a study in simulation and destruction.

I built columns, ran them through Blender’s cell fracture modifier, then staged them mid-collapse. The result isn’t realistic, but it’s strangely elegant… frozen destruction.

I wanted the background to be richer, but my PC couldn’t handle the load. So I scaled back, simplified.

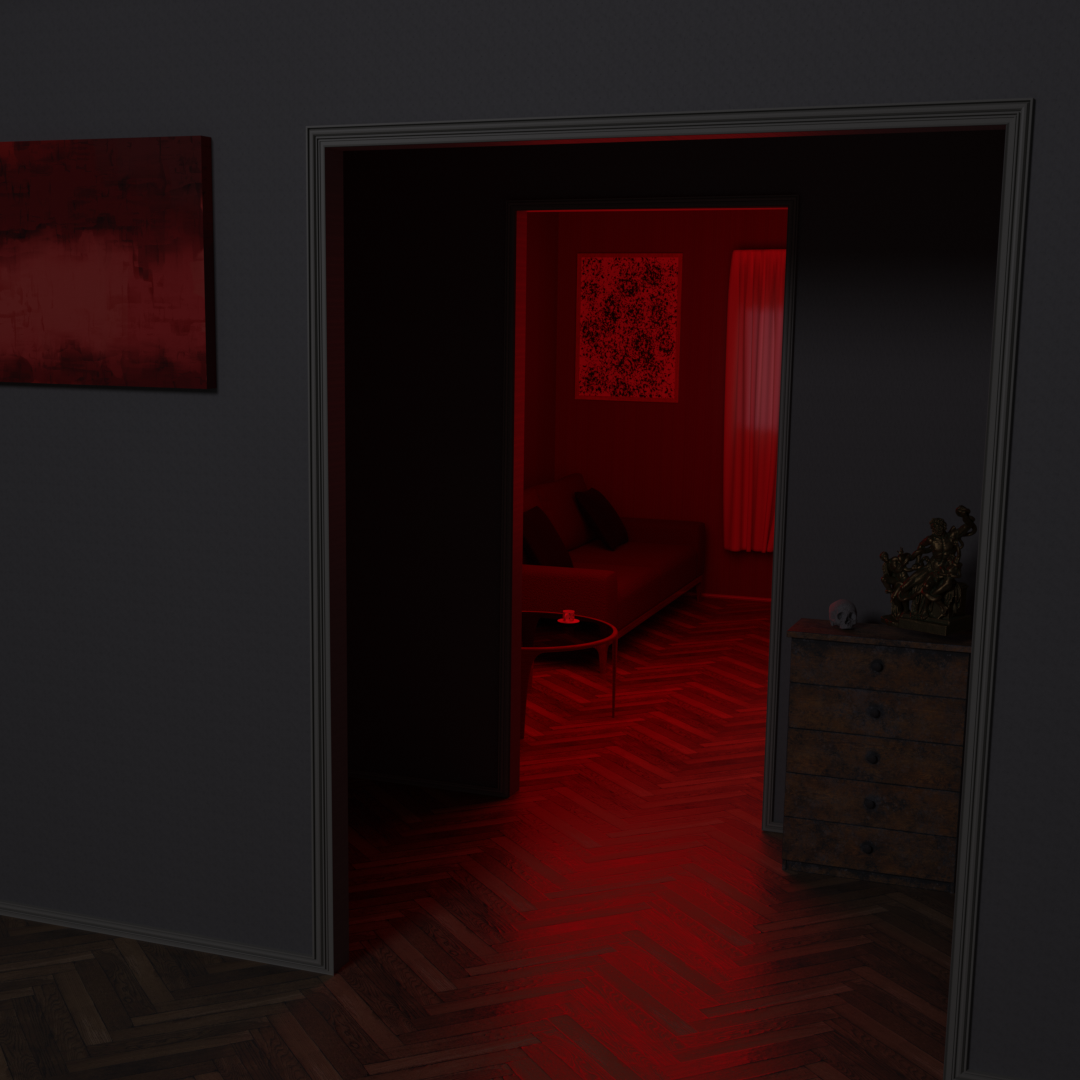

Vertigo Homage

Inspired by a shot in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, the green-lit room where Kim Novak sits shrouded in shadow.

This wasn’t a 1:1 recreation. More of a lighting and composition study. You’ll struggle to find any similarities, but the intention was there.

I played with contrast, shadow cast, deep reds. Tried to frame the room like a character, looming, deliberate, off-kilter.

The proportions are off, and the materials feel unfinished, but that wasn’t the point. This scene taught me that lighting isn’t just for realism, it’s for tone. I began using a few pre-made props, drawers, statues, paintings, not as focal points, but as set dressing to support the mood. Modelling took a back seat. The real focus was staging: camera placement, shadow direction, emotional weight. (Though my faithful table did sneak in one last time.)

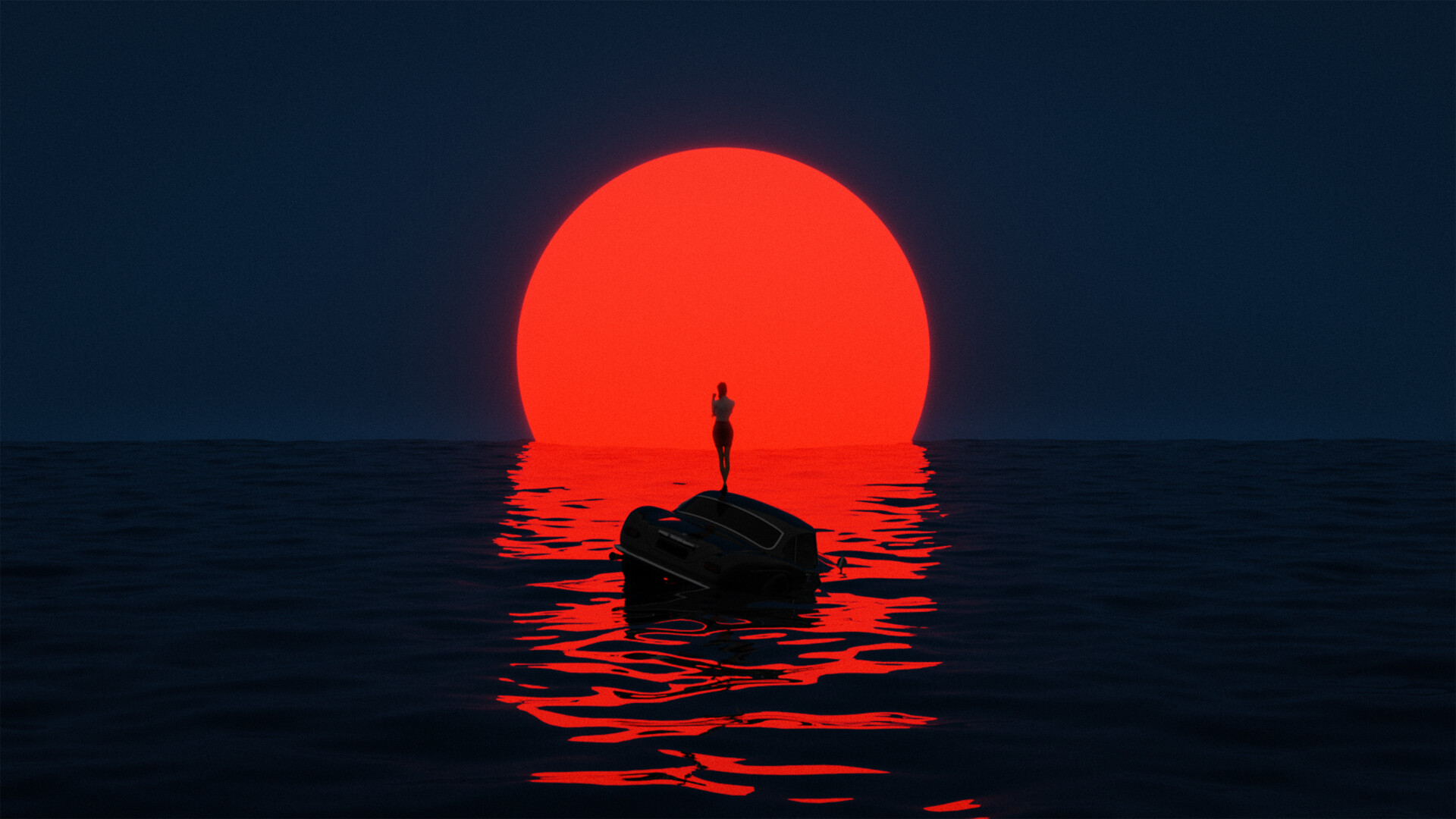

Drowning Sun

This piece came together quickly, a final exhale before diving into my last major project. It’s surreal, minimal, and deeply symbolic. A lone figure atop a half-submerged car, floating in a dark sea, silhouetted by an overwhelming red sun.

I didn’t model the person or the car. But the placement, colour, and mood, that was deliberate.

This wasn’t about technical polish. It was about weight. Emotional weight. The kind you can’t name, but feel somewhere behind your ribs. The absurdity of a car in the ocean. The quiet resignation of the figure. The red sun as both threat and warmth.

The world was opening up again. And this image became a visual punctuation, a moment suspended between lockdown and return.

Oldboy Room (1)

Oldboy Room (2)

This was the last big one.

I tried to recreate the infamous prison room from Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy.

No blueprints. Just film stills and guesswork.

I blocked out the dimensions. Rewatched the scene over and over. Tried to get the bed right, the lamp, the weird artificial layout. But it was draining, like assembling a puzzle where the pieces were blurred.

By the time I got to materials and lighting, I was spent. I cut corners. Pushed through. And still, I’m glad I did.

It’s not accurate. It’s not polished. But it felt like a fitting goodbye, to my room, to Blender, and to lockdown. The veil of pandemonium had lifted.

Final Thoughts – What Blender Left Behind

I don’t remember the shortcuts anymore. I’ve long since forgotten the hotkeys, the nodes, the render settings I used to obsess over.

But I remember how it made me see.

I notice things now I never used to, the way shadows fall in a hotel room, how fog in a film softens the truth of what you’re looking at. I understand that light and emptiness are not just visual tools, they’re narrative ones. They tell stories quietly.

Blender was never going to be my career. It wasn’t about building a portfolio, or reaching an audience, or learning every tool in the box.

It was about creating something, anything, in a time when the world outside was static, frightening, and unfamiliar. It was about control in chaos. Focus in stillness. A place to lose hours and, in doing so, find a little bit of clarity.

More than technical skill, it taught me patience. How to sit with a problem. How to persist when the initial spark fades. How to find rhythm in repetition, even if no one sees the result.

I don’t use Blender much anymore. Life picked up. Other projects took over. But that quiet season of rendering, looping, modelling, and lighting changed how I interact with the world.

And that’s enough.

Blender gave me an outlet. And for a while, it gave me peace.

Many moons later…

Final Render – The Moon

Stillness. Simplicity. And letting go.

After finishing the Oldboy room, I returned to work, no longer was I able to spend hours tinkering away.

However, weeks later, I opened Blender one last time.

No simulations. No concept art. Just a NASA bump map and a sphere.

I applied the texture, lit it with two spots, angled the camera, and rendered.

That’s it.

And honestly, it might be my favourite. Because in its simplicity, it represents what Blender became for me by the end:

Just a quiet place to look at something beautiful.